16 years ago Huygens probe landed on Saturn’s moon, Titan

16 years ago Huygens probe landed on Saturn’s moon, Titan

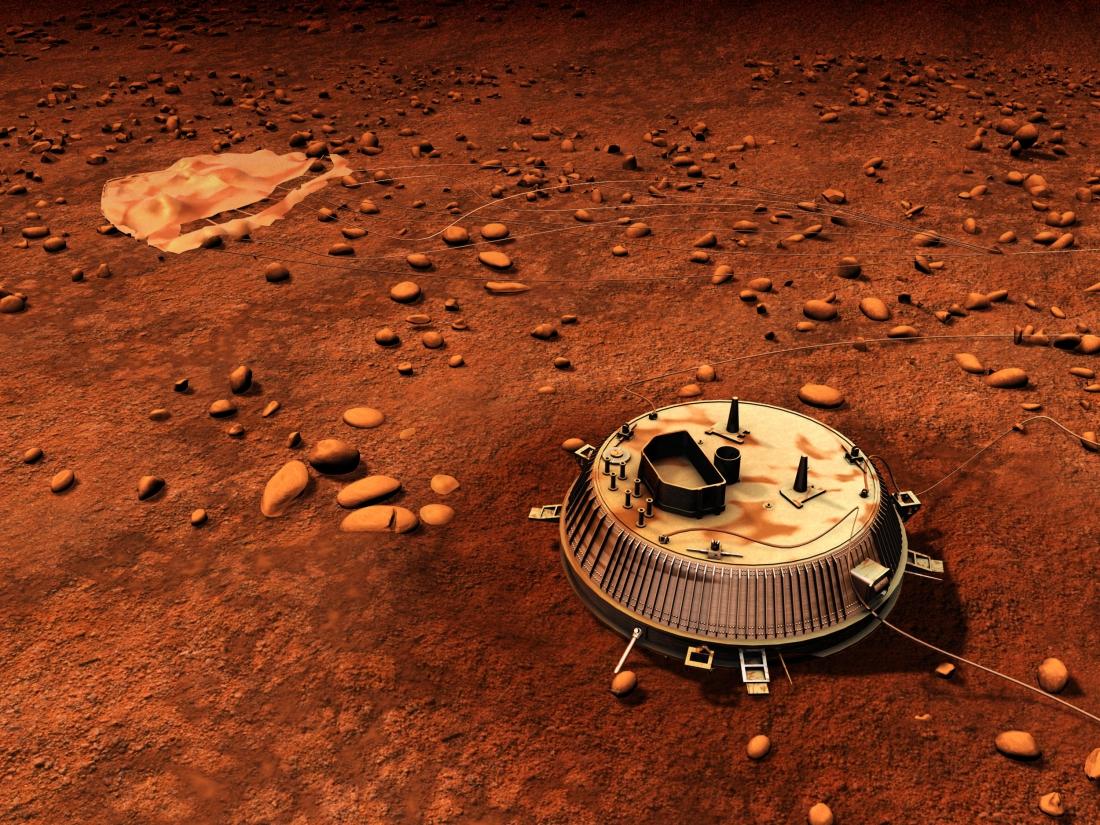

On This Day in 2005 the Huygens probe landed on Saturn's enigmatic moon.

Sixteen years ago, Europe celebrated the success of an exceptional mission, still the only one of its kind: a landing on Titan, Saturn's enigmatic moon, at a far greater distance than any atmospheric probe had ever traveled at the time. The European Space Agency (ESA) had originally selected Thales Alenia Space in 1991 to lead a team of companies from throughout Europe. They rose to the challenge. The Huygens probe, attached to an orbiter, had lifted off on October 15, 1997, and landed smoothly on Titan on January 14, 2005, after a voyage lasting seven years, giving the international scientific community a veritable plethora of scientific information.

A bountiful harvest for a high-risk mission

All data gathered by Huygens during its descent and from the surface of Titan were transmitted to the Cassini orbiter. To pick up this invaluable data, the orbiter pointed its 4-meter-diameter high-gain antenna, built by Thales Alenia Space as part of the Italian space agency’s mission contribution, towards Titan. When Cassini lost contact as it slipped below the horizon of the landing site, the probe kept transmitting signals, which were picked up by large radio telescopes back on Earth. Subsequently, Cassini once again directed its antenna towards the Earth to relay the recorded data. All in all, Huygens operated for 148 minutes during its descent, and for more than three hours on the ground.

For scientists around the world, these 474 megabits of data, including more than 350 photos, were a veritable “manna from heaven”, food for study for scientists from around the world, which continue to be analyzed. It turns out that the dynamics of the Titan atmosphere are comparable to those on Venus, Earth or Mars, enabling us to expand our scope of investigations in comparative planetology, as well as our understanding of planetary atmospheres – especially of our own planet.

The surface of Titan revealed a world modeled by cryovolcanic eruptions, along with precipitation of methane and other hydrocarbons. The measurements of atmospheric conductivity carried out by Huygens, and the information transmitted by the Cassini orbiter ultimately revealed a world of liquid methane and ethane lakes and seas, gigantic sand dunes, ice cobbles and rivers, an ocean of ammonia-rich water under a crust of ice, variable altitude clouds, an atmosphere rich in argon and propylene, and much more.